The climate change talks in Bonn have now wrapped up with little firm action. Next year they move to Poland. But whatever is discussed or agreed in European cities over the coming years, the answers to climate change will not come from the west (beyond a few technological tweaks), but Asia.

Climate change is the most striking example of the unintended consequences of an unsustainable economic model. It is predicted that some regions, such as Asia’s Indus valley, will be too hot to live in by 2100. Coastal megacities are threatened by rising sea levels. Common resources – land, food, water and forests, among others – are already strained. Climate change will upend agriculture, making food security a major issue for hundreds of millions at a time when arable land is in decline.

But climate change is far from the only example of what is wrong with our model of development. Air pollution levels in Delhi were so high over the weekend that an international cricket match was halted, with players reported to be “continuously vomiting”.

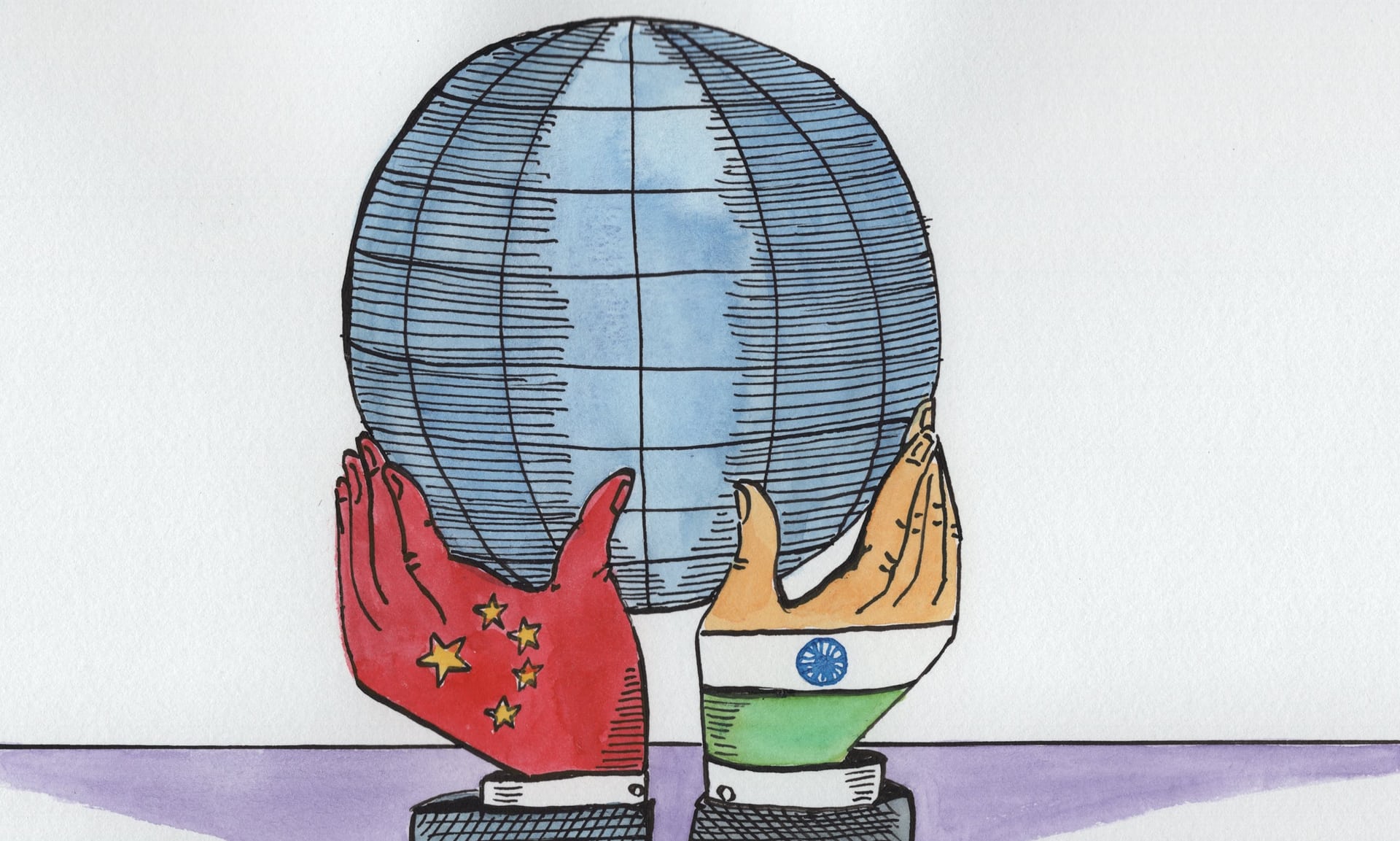

The west isn’t going to sort this out. Its democracies face huge difficulties when confronted by the need for unpopular decisions that dramatically shift lifestyles and mean people must give up privileges such as car and air travel that they have taken for granted. Perhaps inevitably, western politicians prefer to seek solutions through market mechanisms and technological “innovations”. When it comes to the future of the planet, decisions in Beijing, New Delhi, Jakarta and Lagos will be more important than those taken in Washington or Brussels.

With the dual challenges of growth and sustainability, Asian governments face a unique challenge. They have large and increasing populations that are still poor, with a majority still lacking secure access to the basic rights of life: a minimum standard of living that includes a safe and secure food supply, clean water, permanent housing, adequate sanitation and access to energy.

Yet they can’t improve their standards of living in the resource-intensive way western countries did. To do so would be to invite catastrophe. Their common resources are strained and the biosphere is stressed – a situation that, as science makes clear, will only get worse.

Sri Lanka cricketers forced to wear anti-pollution masks in Delhi, during the current Test match against India. Photograph: Altaf Qadri/AP

It is true that Asia is very diverse. A solution in South Korea or Singapore will look very different to what is pursued in poorer Cambodia or Myanmar, or middle-income Malaysia.

But all Asian governments must, in the coming decades, find ways to sustainably manage resources to ensure their populations – current and future – have access to them. They need to develop solutions that move away from what the west believes to be the standard. They need to put more focus on collective welfare over individual rights. They need to manage expectations so as to avoid overconsumption and waste.

So how is Asia doing so far? October’s Chinese Communist party congressprovided reason for cautious optimism. One thing in President Xi Jinping’s three-hour keynote speech stood out: his redefinition of China’s “principal contradiction”. For Deng Xiaoping, widely regarded as the father of modern China, this contradiction was between the nation’s needs and its overall lack of development. Xi now describes it as the tension between “unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever growing needs for a better life”. In this, Xi signalled a move away from a policy of development at all costs towards something more balanced.

This is an approach the other large nations of Asia, such as India and Indonesia, should take note of. Until now, the continent’s imbalanced model of development has been based on prioritising growth in the cities over development in the countryside. Many large Asian cities are becoming intolerable places to live because of congestion, density and heat. Inequality has also increased. And as Asia seeks to embrace modernity – which, in practice, means adopting many aspects of western lifestyles – it risks losing its own culture and traditions, which underpin age-old values and have helped maintain social cohesion over centuries.

From massive solar schemes to decades-long reforestation projects designed to hold back the desert across the western part of China and inner Mongolia (the Great Green Wall of trees is aided by a solar power station), the Chinese government is leading the fight. Vietnam too has taken steps towards sustainability, investing in rural irrigation to increase rice yields. In the Philippines, President Duterte has taken a hard line against the excesses and poor regulatory oversight of the mining industry, despite resistance from powerful lobby groups.

Singapore is a much smaller and wealthier example, yet despite its “free market” reputation it routinely takes wide-ranging action to ensure that housing, healthcare and other social services are provided universally. Nor is Singapore scared to make aggressive interventions that would be decried as socialist in parts of the west: the government announced in October that it would put a hard limit on the number of cars in the city.

These countries need to go much further in developing new economic models if the world’s resources are to be sustained. But Asian governments must not act alone. The region has several international organisations and blocs that can encourage the sharing of ideas.

Developing nations must be given room to find alternatives by the mainly western-led international rule-making organisations, and must not be lectured by western leaders who have no experience in dealing with these challenges.

But most importantly, Asian policymakers and business leaders must start to take the lead, and stop being subservient to western ideas about progress.

Avots: The Guardian