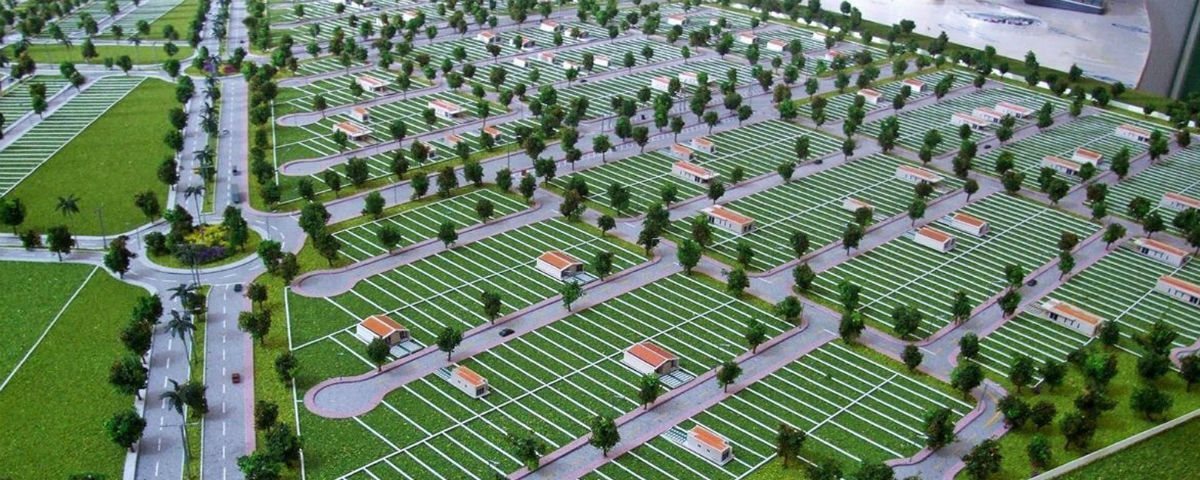

In 2017, ArchDaily Brazil reported that Smart City Laguna would become the first “smart city” in Brazil. With its inauguration scheduled for that same year, the venture opened with 1,800 units in its first phase, and in its final phase, 7,065 units divided between residential, commercial and technological uses.

Located in the Croatá district of São Gonçalo do Amarante, the first Brazilian smart city occupies 815 acres directly connected to the federal highway BR-22, which crosses the states of Ceará, Piauí, and Maranhão, starting in Fortaleza towards Marabá, in Pará. Its location has economic reasons: the proximity to Pecém Harbor, in Fortaleza, the Pecém Steel Company (CSP) and the Transnordestina Railroad make Croatá a strategic hub that has been recently occupied by technological companies, becoming a “digital belt” a little over 50 kilometers from the state’s capital.

The self-proclaimed first social-smart city in the world is a development by the Italian group Planet. It offers plots for all income brackets, including units for the Minha Casa Minha Vida program (a social housing program in Brazil for low-income families). Also, the project is within the same framework of other smart cities around the world. It is based on technological, sustainable and mobility principles.

Put on the market in 2015, already 2,000 commercial and residential units have been sold. Another 1,500 units have been marketed, according to Diário do Nordeste.

Its success isn’t associated to the amenities of living in a smart city, however, as tempting as the idea of living in a city where many things can be controlled by a phone app, it seems that the most convincing explanation for the numbers is in the land valuation. From August 2015 to November 2017, the residential square meter went up 140.9% whereas the commercial went up 218.2%. People who bought in 2015 seemed to have made a smart investment.

The lots that have undergone tremendous valorization are single-family homes of one or two floors. Would they have undergone such valuation if they were aiming for high density? Probably less than the current numbers, as the Laguna doesn’t exist as a city yet. Therefore, before creating value through density, it needs to be minimally occupied.

To densify areas that are provided with infrastructure is, however, necessary in cities that aim to make good use of its resources – or to use them smartly – which makes one question the low-density choice in a self-proclaimed “smart” city.

This is not the only point of issue in Laguna. On its website, Planet argues that “the goal is to reach sustainability, safety, and a high quality of life.” Also, that people’s lives in smart cities or neighborhoods are “more economic compared to traditional neighborhoods, as well as more sustainable and inclusive.” There are no indicators, however, that explain how making a new city from scratch alongside a highway can be more sustainable and inclusive than occupying spaces in a preexistent city which already has the infrastructure and presents the social dynamics of a consolidated urban agglomeration.

The website explains, a little further down, why they chose Croatá, telling the reader the main founding principle of Laguna: investments. It is not at all wrong for a city to seek investments; all of them do with more or less voracity. The problem is for Laguna to call itself smart when in reality it is a traditional neighborhood – designed, but – surrounded by the advertising rhetoric of a smart citywhich turns devices and technological innovations into the solutions for urban problems.

In an era where ideas such as urban acupuncture or small-scale projects offer effective means to turn our cities’ problems into environmental solutions, building a city from scratch – from infrastructure to application – can be anything but smart.

Avots: archdaily