One of the most exciting product announcements to happen at the Consumer Electronics show over the past few years was the Gogoro electric scooter. It’s not just that it was slick-looking, or fast, or that the company was promising a clever battery swap station model to help ease the problem of charging. On a broader level, much like Tesla’s electric cars, the Gogoro scooter felt like the best representation of an idea that was already kicking around but hadn’t been fully executed. It felt like the first smart, sharp, two-wheeled electric vehicle.

Gogoro’s scooter came at a time before the world’s biggest automakers started making multibillion dollar promises about electrifying their fleets. And even then it felt like a sign. If Tesla could tip the auto industry toward electrification, surely a company like Gogoro could do the same for the scooter market, where problems like air (and noise) pollution are still rampant.

Since Gogoro came out of stealth mode, Yamaha, Honda, even Piaggio — the world’s most recognizable scooter company and the maker of the vaunted Vespa — have signaled that they’re shifting to electric (and in some cases, hybrid) technology. BMW was already doing itbefore Gogoro appeared on the scene. But one particular announcement from last week feels like the first real break in the dam.

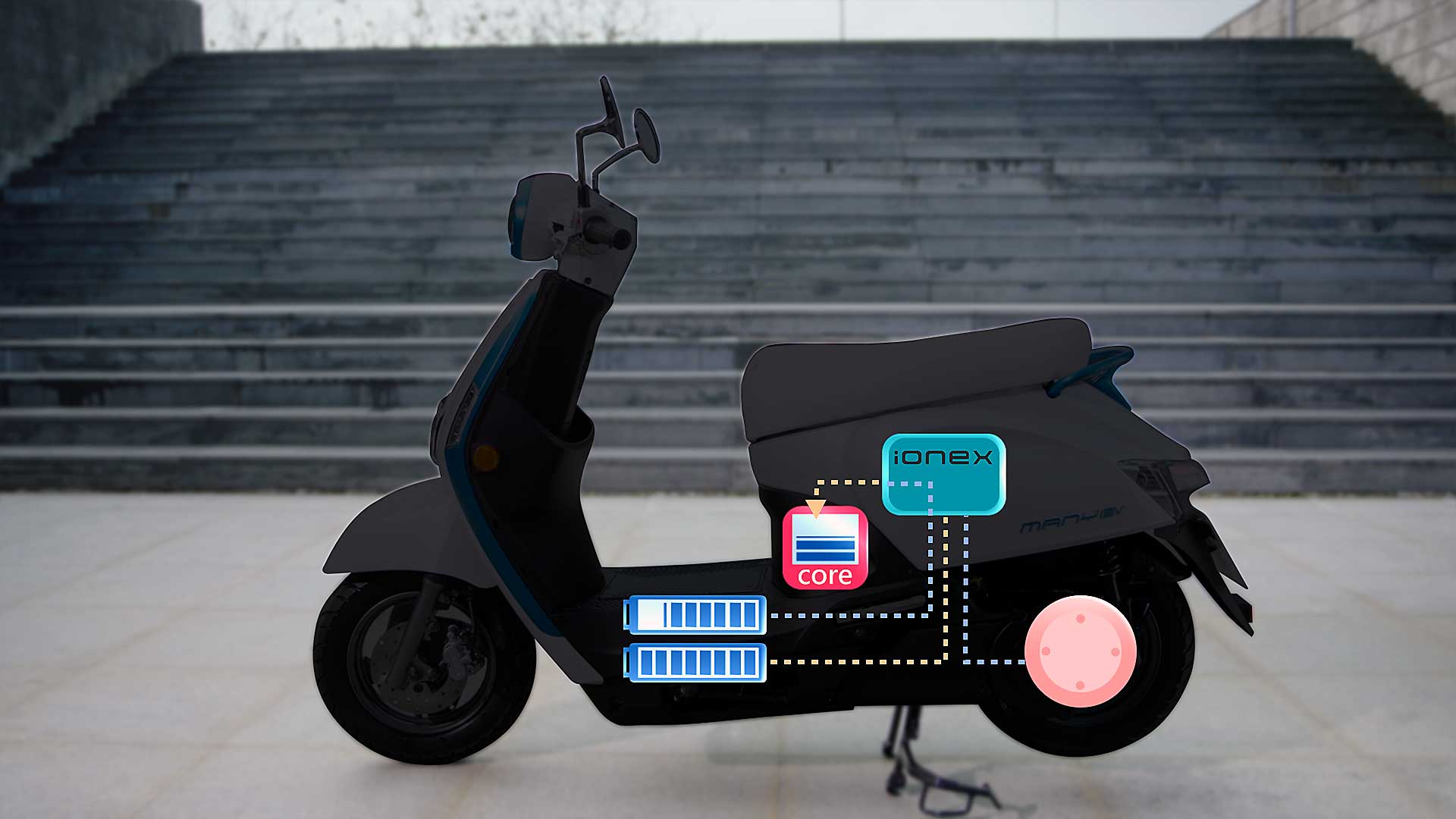

Kymco, the largest two-wheeled manufacturer in Taiwan, announced a pair of all-electric scooters with swappable batteries. It’s the company’s first foray into electric drivetrain tech for its two-wheelers. But unlike Piaggio, which has been mostly mum on the electric Vespa since it was announced in late 2016, Kymco appears to be embracing electrification in a big way.

The two Kymco scooters are tailor-made for city life, meaning they’re not going to blow you away with wild speed or bountiful range. The Nice 100 EV is the cheaper scooter, costing around $1,400. It has a top speed of 28 miles per hour and a range of about 37 miles. The New Many 110 EV is $1,600, and for that extra cash riders get a higher top speed of 37 miles per hour. And those prices are after local subsidies.

While the scooters might lack punch, Kymco is at least trying to get around the range limitations by promising to build a network of battery charging stations that’s reminiscent of Gogoro’s in its design. In fact, the move feels purposeful to Ryan Citron, a senior research analyst at Navigant Research.

“To me, this screams that there’s concern over Gogoro’s success, because Gogoro actually has been pretty successful when you think about electric scooter manufacturers,” Citron says.

Gogoro’s success has blossomed since that 2015 debut. It closed a $300 million round of funding in late 2017. It’s sold tens of thousands of scooters, enough to give it 92 percent of the electric scooter market in the cities that it operates in, according to the company. (Overall, Gogoro says electric scooters make up about 6 percent of total scooter sales in these markets.) It runs scooter rental services in Berlin, Paris, and Japan, and it’s set up more than 400 battery swap stations in Taiwan. CEO Horace Luke told me last year that battery kiosks are a big driver of the company’s growth, with more than 17,000 batteries swapped per day.

There’s a key difference in how Kymco’s stations will work compared to Gogoro’s, though. With Gogoro’s battery stations, you drive up, drop your batteries into an empty slot, take new ones, and go. With Kymco’s, the idea is that you’ll drop your batteries off to charge, with the scooter running on an internal battery in the meantime. Around one hour later, you can pick the batteries back up, fully charged.

“For me, that’s a major downfall compared to Gogoro,” Citron says. “It’s kind of bizarre.”

Fortunately, Kymco has a few other ideas. The scooters have enough storage to fit three extra batteries. Owners can rent extras on a per-trip basis, and the scooter’s storage can hold up to three extra batteries, so it’s theoretically possible to imbue the scooter with about 120 miles of range, the company says. There’s also a home-charging dock for the batteries, so it’s possible that many owners might not have to bother with the battery stations in the first place.

Battery strategy aside, Citron says this is a “pretty significant” move because Kymco is a such a big scooter provider in Taiwan. And the company’s ambitions go well beyond the first two EV models. In a release, Kymco Chairman Allen Ko said the company plans to launch 10 electric models over the next three years, set up charging networks in 20 countries, and sell “over half a million electric vehicles worldwide.”

It’s not surprising that Kymco is taking such an aggressive approach, Citron says, because there’s great economic potential for electric scooters, specifically in the Asia Pacific region. Globally, though, Citron expects the category of “light electric vehicles” — which includes electric motorcycles and low-speed limited EVs, as well as electric scooters — to grow from a $9.3 billion market now to a $23.9 billion by 2025, according to a research note he published with Navigant in 2017.

Driving people to believe in electric tech can be a challenge, but Citron says the biggest barrier will be price. Electric scooters are still more expensive than gas scooters, which needs to change in order for there to be any adoption, and companies can’t always count on government subsidies, he says. What’s more, some cities are already looking to banscooters and motorbikes because of pollution and safety issues. So, Citron says, “the question is going to be how soon can they compete?”