In the world of impact capitalism, opportunities don’t come much bigger than sanitation. More than 2 billion people go without the dignity of a decent daily toilet; two-thirds of the world’s human waste isn’t disposed of safely. As a new report shows, there are big gaps for startups and big companies to fill with new services and business models, and tremendous potential to make money and do good at the same time.

The Toilet Board (TBC)–a coalition of companies like Unilever and Kimberly-Clark, development agencies, and nonprofits–has been scoping out the emerging “sanitation economy.” The report categorizes openings and outlines how new business approaches can take the place of traditional grant-based sanitation programs.

“We want to see how we can help these companies, rather than just give money to NGO,” Cheryl Hicks, executive director of the Toilet Board tells Fast Company. “We’re trying to move them away from donor-dependency to commercially viable, scalable, and replicable business models.”

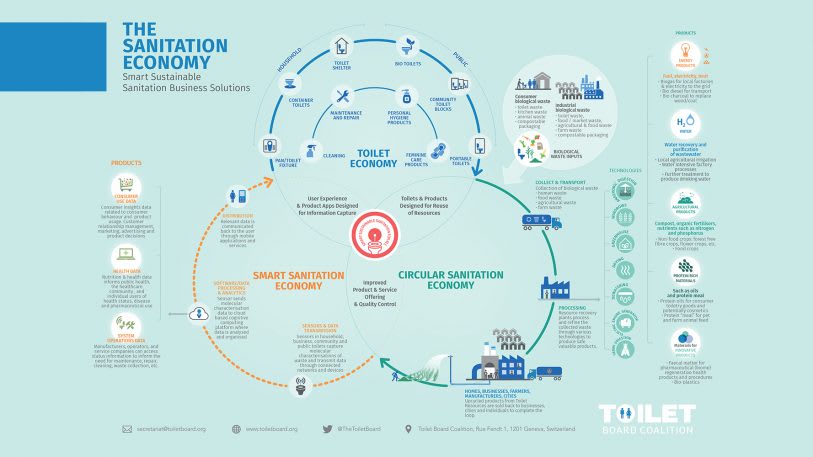

There are three big buckets of market opportunity, according to the report.

First, there is a need for cheaper, safer toilets themselves, like the SaTo toilet developed by Japanese toilet giant Lixil, and designs funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; accessories like personal hygiene products; and, perhaps, building developments around toilets. “The most interesting companies are realizing marketplaces around toilets,” says Hicks. In India, Samagra is building a network of toilets within mini-malls of services, including phone charging and financial services. Here’s Samagra’s US-educated founder, Swapnil Chaturvedi, talk about the challenge of building a profitable toilet business.

Then there’s the circular economy of sanitation. The world produces 3.8 trillion liters of human effluent each year (an average of 500 liters per person per year). Much of this potentially valuable resource is currently wasted, instead of becoming products like fertilizer, biogas, electricity, water, protein-rich materials, and pharmaceuticals. But there are startups emerging, like Safisana in Ghana that is converting human waste to fertilizer. GENeco, a waste-to-energy company owned by Wessex Water, a utility in the southwest of England, has produced the first car powered by human waste (actually by biomethane), as you can see here.

Third, there’s the possibility of exploiting sanitation-level health data, Hicks says. Researchers with MIT’s Underworlds project are putting sensors down sewer pipes, mapping the poo-and-pee bacteria of whole city districts, most recently Seoul, South Korea. TBC’s own smart sanitation showcase in Pune, India, is gathering and analyzing health-related data from home toilet bowls.

It’s still early days for many of these companies and projects. Hicks says the sanitation economy needs support from corporations like Unilever (which is involved with the Pune project) as well as seed capital and ecosystem support, so startups can grow and become viable.

“There’s a lot of interest in the sanitation space among impact investors. There could be real deal flow in the future,” she says. “It’s our job at the Toilet Board to see that the startups are replicable and then get investors interested.”

Avots: Fast Company