There’s 80 times as much gold in one ton of cellphones as there is in a gold mine, says Federico Magalini, an expert on electronic waste. That means there’s enormous potential for recycling — and yet, most of us keep our old electronics at home.

Lately, there’s been a lot of interest in old electronics. Last week, Apple debuted Daisy, a robot that disassembles old iPhones to recycle the materials inside. Reuters covered a South Korean factory that specializes in retrieving precious metals from car batteries. And in a recent paper published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, researchers argued that recovering materials from discarded electronics — often called “urban mining” — makes more financial sense than mining for new materials from the earth. (Though sometimes, e-waste doesn’t end up where it’s intended.)

But what exactly is e-waste? Is it just phones and batteries? Where does our laptop go when we do recycle it? How much can we gain from recycling, and how is “urban mining” changing? To answer these questions, The Verge spoke to Magalini, an e-waste researcher who is also managing director at United Kingdom sustainability firm Sofies.

The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

What is electronic waste? We think of old phones and old laptops, but is that definition too limited?

The best definition of e-waste is any product you discard that is still working, is connected to a plug, and has a battery. This also includes devices that generate electricity, like solar panels. It’s a lot of products, and people should think more about how many of these gadgets they have in the house. The number is about 80 devices per family. But when you tell people, they don’t believe you.

So I say, just take a piece of paper and start counting. When you finish this list, you should go back and think again about what you have in drawers and you will find 10 to 15 products minimum that you didn’t think of at first, like an electric toothbrush or power tools or lamps. It’s unbelievable.

I’ve seen statistics saying that electronics is the fastest-growing source of waste and the problem is getting worse. I’m probably part of the problem because I never do anything with old laptops. I just keep them around.

Yes, exactly. That’s the problem. Think about it: you don’t store food waste at home, or plastic waste or packaging. You get rid of it as soon as possible. But electronic waste is different. It’s easy to find a place to store them, unlike with food waste. And we are emotionally attached to our phones, PCs, and cameras, so it’s difficult to throw these gadgets away.

Plus, even if they are broken, sometimes people still keep them. That’s a huge amount of material that is not entering the recycling chain. Every one of us, without thinking, is keeping this at home and preventing natural resources from going back into the economic cycle.

The idea of recycling e-waste or doing “urban mining” isn’t new, right?

It’s not a new trend, but the term “urban mining,” has been introduced recently to explain one particular concept. Take the example of gold. Gold is present in nature, and, on average, the concentration of gold is about 0.5 grams of gold for every one ton of material. So if you go in your garden and start digging, after you make a big hole and dig out one ton of material, you have the chance to find half a gram of gold. That’s the average concentration on Earth.

Of course, in some places, gold is more concentrated, like gold mines. So, there, you dig one ton of material, and you can find five or six grams of gold.

Now, if you look at how much gold you have in a single mobile phone, it’s obviously not a lot. But in one ton of mobile phones, there is usually about 350 grams of gold. That’s 80 times higher than the concentration you have in gold mines. That’s why we call it “urban mining.” We say it’s much more efficient to extract gold from electronic waste. It’s much more concentrated.

What are the materials we’re trying to retrieve? Are they all metals?

The majority of electronic waste is metal-dominated: iron, copper, aluminum, and then plastics, of course. In much smaller amounts, you have more precious metals like copper, silver, gold, palladium, iridium, and rare earth metals. And all those fancy technology metals are widely used by the electronics industry. There’s lithium, cobalt…

Historically, metals have value, and you can recycle metal forever. For plastic, it’s different because every time you recycle the plastics, the mechanical properties don’t necessarily remain the same.

What’s the life cycle of something like a laptop? Where does it go?

In Europe, the manufacturer pays for the proper collection and recycling of the waste generated by the product. You can return your old laptop to the shops where you buy the new one or bring it to the local municipal collection point.

If you are in the US, the system is different depending on the state. If you’re in California when you buy a new laptop, you pay an extra amount of money that’s visible in your invoice. It’s maybe two or three bucks. This money is going into a fund managed by the state government of California, and then it’s being used to ensure recyclers and people collecting waste are being paid for their services. In other states, the system is more close to what I described in Europe, where producers are required to pay for the pickup.

What happens after you recycle your laptop, either at the store or a recycling center? And what kind of qualifications do you need to do this job?

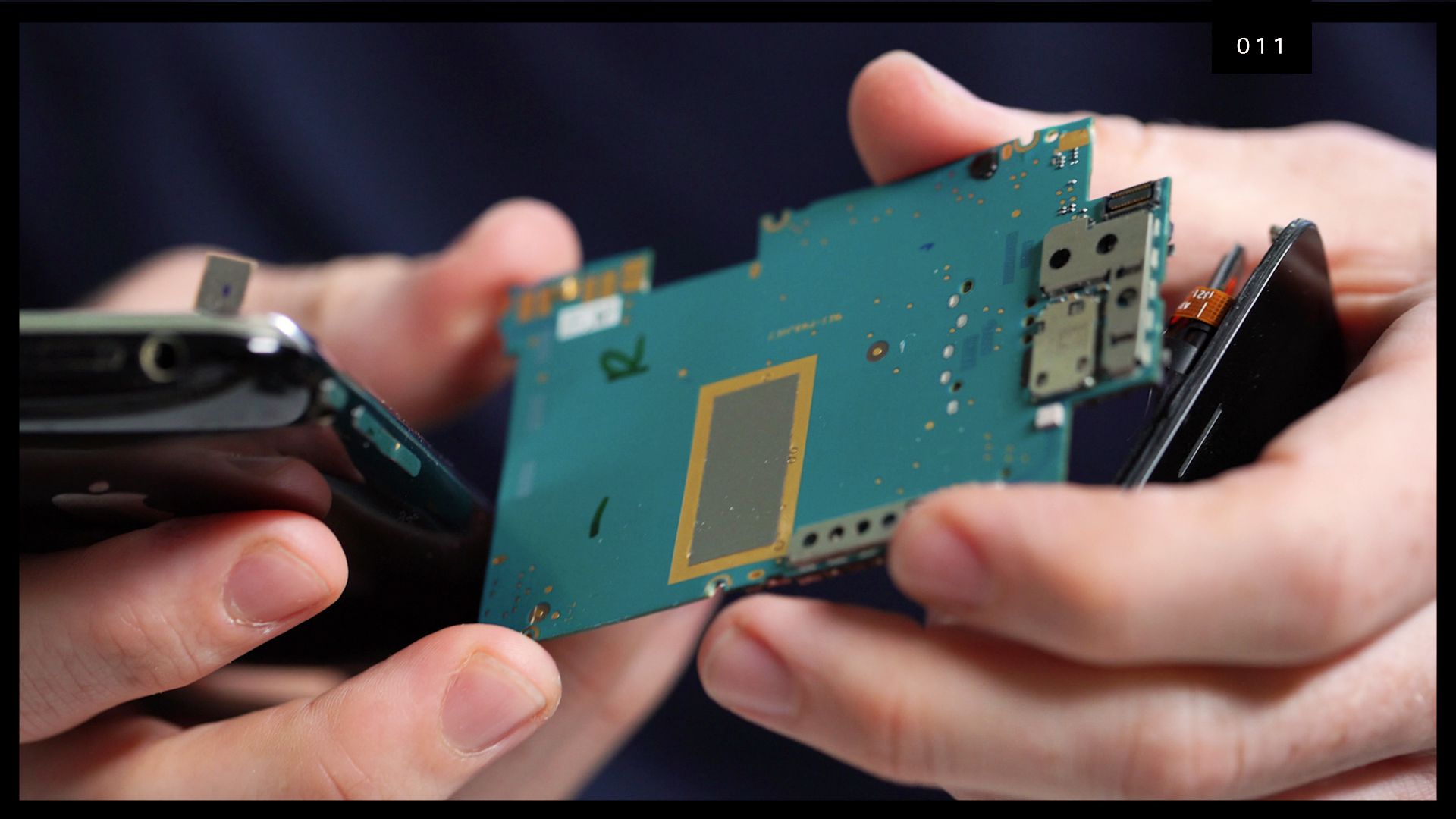

You have transporters who take the laptop to a recycling plant where it is disassembled. It’s basically shredded and then the different components are sent to other dedicated players, like a center that is recovering precious metals or a center that is recovering plastic.

For this first part, manual disassembly, you don’t need to be an engineer to do that, though you need to be trained to do it properly. With laptops, you really need to be careful with the monitor because in all monitors you have the backlights, and you need to be very careful not to break them and to contaminate them with mercury. But apart from the screen of the laptop, devices like the motherboard, the keyboard, modems, and printers are just broken into small pieces and sorted and each fraction goes to someone else.

You have usually two or three companies in sequence to go back to the real material, which is eventually used to produce something else. When it comes to iron and copper, it’s going to a furnace to be remelted. Circuit boards go to more complex areas to recover the gold and platinum. The type of recycling really depends on the type of material. And, of course, in some cases, there are people collecting the products to see if they’re suitable for refurbishing instead of being shredded and recycled.

What are new tech developments that make e-waste easier?

Recycling — especially when it comes to the recovery of precious metals — is as complex as the production of them. If you visit the facility where they recover precious metals, it’s really high-tech. You have engineers who start designing the technology and processes of recycling.

We see, for instance, companies in Europe trying to find a way to automate breaking down an LCD because it’s a labor-intensive process to manually disassemble it. There is technology being developed to recycle old CRTs [cathode-ray tubes, used in monitors]. People are trying to get smarter to access the economic value of the product more quickly. At the same time, we design new products every year, and those products are becoming waste. And we don’t yet have the technology to recycle the materials that we are designing and selling today, so it’s a constant trend and evolution to improve the efficiency of the process. The reality is that 20 or 30 years ago, we had only a few electric products at home. And in the last 15, the electronic and plastic components have been increasing.

From an environmental perspective, is it still better to fix your old phone than to get a new one, even if you recycle?

From an environmental perspective, it’s always good if you keep the products longer because it means new natural resources don’t have to be extracted. But having said that, as long as you make sure that you discard your old phone and the material is kept in the loop, it’s not that bad.

Recycling can create jobs, and recycling done in the right way can be a profitable business. There is a good opportunity to keep our environment clean, to keep resources in the loop, so there are societal benefits in recycling. The worst thing that can happen is that we keep producing new phones and all the discarded ones are just staying in our drawers because resources are limited. If we keep those resources in our houses, hidden, then we might face a supply chain problems or restriction in the near future.

Avots: The Verge