Mary Beth Foster has three Google Home units throughout her Mint Hill, N.C., home, and her two-year-old often talks with them, walking up to them as if they are another person.

Recently, while her husband took a shower, her son had an entire conversation with the device. “He asked it to play music, and it did,” she said. “And he asked what the weather was. I guess he heard us do that. It told him it was cloudy. And then he asked, ‘What’s a cloudy day?’ And it defined it for him.”

Foster chalks up these discussions as a funny fact of modern life. His first words were “OK Google,” after all.

But these kinds of interactions also are fueling new research and questions about the relationships kids are forging with the robots and voice-activated assistants in our homes. According to a March report released by Common Sense, four in 10 parents of kids ages 2 to 8 say their families have a smart speaker. Of those, 32% say their kids talk to their smart speakers a few times a day — 6% say a few times an hour or more.

“We are such social beings. It doesn’t take very much for us to think, ‘Oh yeah, this is social,’” said Rachel Severson, an assistant psychology professor at the University of Montana. “Even if we know how it works, we can get so easily sucked into thinking about it in this way.”

Stick meet robot

Kids have always had imaginary friends and endless conversations with a stick, a stuffed animal or a character that they’ve conjured up on their own. These relationships are a critical part of development, benefitting social understanding and executive function.

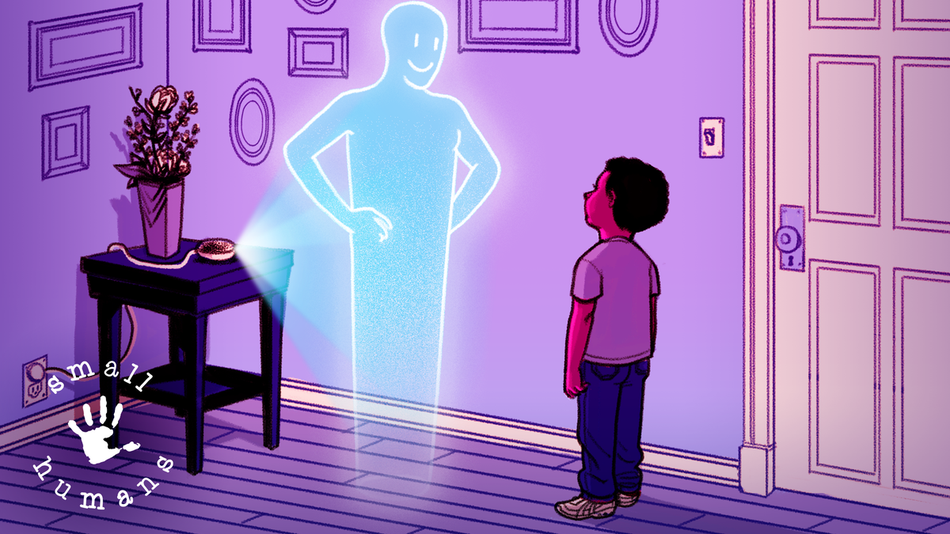

But to the minds of some young children, these new technologies—and the personas they project—can be confusing. They aren’t passive like a doll. And they don’t allow for full creative control like an imaginary friend.

Instead, they’re more like a person. They respond to a name. They tell jokes. They appreciate politeness. Both Amazon’s Alexa and Google have plug-ins that reward users when they say “please.”

And kids see their parents interacting with them — a lot. According to a Nielsen survey, adults’ use of smart speakers peaks in the early and late evening— traditional dinner and bedtime hours. Nearly 70% talk with them “for fun.”

Companies are capitalizing on these new habits. Amazon has an Echo Dot designed for kids. Chatterbox, a build-it-yourself smart speaker kit, is marketed as a “friendly voice assistant” for kids. And Pillar Learning launched Codi, a screen-free “smart DJ” that’s marketed as “your child’s best friend” for kids ages 12 months and up.

To boost engagement, Dayu Yang, Pillar’s co-founder and CEO, said some have encouraged him to gamify Codi, which provides parent-approved content. But that’s not his objective, Yang said. The aim is to build a toy that becomes a companion because it provides useful and engaging material to kids.

“We haven’t heard of any issues where parents might say, ‘I’m really worried about my child’s addiction to Codi,’” he said. “But it’s definitely on top of our minds and we want to make sure we do it responsibly.”

‘Like a friend’

As technology rapidly becomes more sophisticated, researchers who study how kids perceive robots and virtual personas are playing catch up, and starting to provide some insights.

At the MIT Media Lab, researcher Jacqueline Kory Westland writes that kids often treat robots “like a friend,” showing affection and sharing stories. The more “relational” a robot was, the more kids engaged with it and learned from it.

“They were more likely to say that playing with the robot was like playing with another child,” she writes. “They also were more confident that the robot remembered them, frequently referencing relational behaviors to explain their confidence.”

According to research by Severson in Montana, some kids may be predisposed to believe robots have human-like behaviors. She found that kids who have imaginary friends are more likely to believe that technology, including a robot, computer and car, has emotions and thoughts. “Consistently, the robot looks, in some ways, more like how they think about animals,” she said.

And while parents may be eager to buy their kids the latest tech toy, another study indicates that kids don’t necessarily prefer a virtual dog over a stuffed one. Kids say the virtual character is fun and entertaining, but the stuffed animal is the one they want as a friend, said Naomi Aguiar, an assistant psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin Whitewater.

Caution advised

So, what does this mean for families with smart speakers in every room? Experts advise some caution.

Aguiar recommends being mindful about your own tech use and setting appropriate boundaries for the entire family, like smart speaker-free times. And, she said, question any marketing claims about a device’s benefits.

“It’s possible for a lot of these things to become addictive because they are so gratifying,” she said. “Be skeptical about anything that [promises] to promote opportunities for learning.”

Severson suggests parents talk with their kids about how smart speakers really work. And, she reminds parents that gadgets shouldn’t replace simple toys, unstructured play, and time with actual humans.

Think carefully, she said, about those parenting moments you might be outsourcing to technology — having the smart speaker read a bedtime story to your child instead of snuggling with them yourself.

Sure, reading the same book every single night can be mind-numbing. “But, it’s also, this is going to go away at some point and I’m going to really miss it,” Severson said. “I project myself into the future to remind myself that, in this moment, I do want to be here.”

Avots: mashable